Critical Introduction

As a literary genre nonsense has been frequently used to create compelling and mystical lands, creatures and stories that excite and baffle readers. The true amount of nonsense literature that has been created is massive, but despite this as a genre it is notoriously overlooked and misunderstood. Texts such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll are universally understood as being nonsense literature. However, there is a vast collection of other nonsense literature that many people have never read or even heard of, some of which this anthology aims to show. Due to Disney’s adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass these classic novels are widely loved by people of all ages and cultures. Published in 1865 and 1871 respectively they signified the new ideas of the era in relation to children and their role in the family. During the Victorian era children were not considered children in the sense they are in modern day society. Children were expected to work doing manual labour and potentially dangerous jobs such as chimney sweeps and factory workers in order to earn money for the household as many families couldn’t afford to live without their help. This expectation meant that the idea of the ‘child’ as something young and carefree was virtually unheard off, especially in working class households. When Carroll published his works about Alice it stood out from other novels of the decade, such as Tom Brown’s Schooldays by Thomas Hughes published in 1857. This was because Carroll wrote in a manner that defied logic and structure and allowed a child’s imagination to run wild, as opposed to novels such as Hughes’ which aimed to teach children moral and social lessons.

A standard definition of nonsense is virtually impossible to find as it appears nonsense means different things to different people. Susan Stewart describes it as “an activity by which the world is disorganised and reorganised”.1 She also believes that “nonsense can be seen as an aid to sense making”. (Stewart, ‘Nonsense’, pp.5.) Hugh Haughton has also written on this topic and states that “the term ‘nonsense’ is mainly used to police the frontiers of acceptable meaning and establish the limits of significant argument”.2 His description of nonsense as “policing” language and meaning is interesting as it implies he gives a great deal of power to nonsense as a literary genre and its ability to create questions and encourage change. Perhaps the most poetic, Carolyn Wells describes nonsense as “a small and sparsely settled country, neglected by the average tourist, but affording keen delight to the few enlightened travellers who sojourn within its borders.”3 This appealing metaphor shows Wells’ positive view of nonsense, particularly as she describes it’s avid readers as “tourists”, which implies that nonsense is more than just literature as it can teach us and expand our horizons. She also describes the readers as “enlightened” showing her belief that we are better off because of reading nonsense. These are all strong and opinionated views from literary professionals who clearly enjoy what nonsense gives them, however they are all nonetheless different interpretations. The main problem that occurs when attempting to define nonsense in a clear-cut and structured manner is the fact that nonsense is, at it’s heart, neither of these things. Nonsense is colourful and loud and rejects all boundaries and conformities. It is not self-conscious in it’s language and does not concern itself with pre-determined literary and psychological expectations. It does not aim to be understood and analysed. Nonsense is truly free and flexible to be anything a reader interprets it to be. It is expression in it’s most existential form and encourages a reader’s imaginations to flourish. Nonsense also usually tends to focus on fairly simple plots that a reader can easily connect with and relate to, thus the appeal of nonsense is, in theory, endless.

As previously mentioned nonsense is one of the less popular literary genres despite the amazing poetry and prose it boasts, much like the pieces in the following anthology. The general knowledge of nonsense literature is of writers such as Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Middle aged, middle class, white males writing in Victorian England. Their work is exceptional and no doubt deserves the praise it receives, however there are many other cultures who have created equally intelligent and impressive nonsense literature that do not receive this world wide acclaim. In this respect, nonsense can be seen as limited. Susan Stewart writes about this in her book Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. She says “The procedures used in making common sense as well as the procedures used in making nonsense so clearly parallel certain linguistic devices […] that I am sceptical of any claim that they are cross-cultural or universal.”(Stewart, ‘Nonsense’, pp. viii.) Here, Stewart suggests that the correlation between culture, language and nonsense is profound and in doing so she highlights that a universal critique of nonsense would be impossible. Language is the basis for all literature, but is often especially significant in nonsense due to phonology, word-play and cultural jokes. Therefore a distinct language will have features such as rhyme and alliteration that do not transcend language barriers and so when translated may not have the same effect, as I will discuss later.

Culture forms the basis for this anthology as it is a showcase of some less well known work of nonsense poets from Bengal in India, such as Sukumar Ray who was writing in the late nineteenth century. Another key factor is children and nonsense. The pieces I have selected are all great examples of Bengali children’s nonsense poetry, and despite the cultural and language differences they share many similarities with that of English nonsense poets such as Lear. At the heart of these poems is an emphasis on nursery rhyme and folk stories that can entertain both adults and children. Bengali nonsense literature from this period is also heavily influenced by the authentic and spiritual Bengali culture. Michael Heyman, in his book The Tenth Rasa, suggests that a significant role of children’s nonsense from all cultures is to introduce children to the potentially frightening and “awful” things in the world but in a controlled manner that removes any threat they might feel. He writes “perhaps nonsense, regardless of the language, allows children to engage safely with the ‘awful’, but also takes away their fear of it.”4 I find this interpretation interesting as nonsense often encounters adult themes and ideas, such as death and misfortune, that children are typically sheltered from. Content such as this is usually not dealt with in children’s literature due to the potential to frighten or upset young children. However, I would agree that nonsense has the ability to address these topics within the secure boundaries of a poem or story and so can help familiarise children with these difficult concepts and aid their understanding.

In the mid nineteenth century, India was in the midst of the Bengal Renaissance which was “a period of social upheaval” by which many “upper-class Indians had access to western education”.5 This lead to a great intellectual growth in the country and an increase in Bengali literature, art and music. Prior to this Renaissance there was a limited amount of interest in writing for children, however afterwards the intrigue in “the development of the child’s mind” lead to an increase in literature for children. (Bond, ‘Wordygurdyboom!, pp. The India Pages.) The origins of Bengali nonsense, as observed by Michael Heyman and written about by Ruskin Bond in Wordygurdyboom!, derive from two different schools of writing. One being folk literature such as children’s lullabies and the other being sacred texts. Heyman writes that “various re-tellings, contortions and expansions of the basic form [of folk literature] build on the amusing sense of absurdity found in the un-‘enlightened’ form.”( Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xxxii) Here Heyman explains that Bengali nonsense was born out of an enjoyment of innocently removing the imposed rules and rigidity of folklore and scared texts in order to create something that does not give answers but instead helps us to accept “such opposing dualities, even to enjoy them”.(Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xxxii). Despite this growth in popularity Bengali nonsense didn’t, and still doesn’t, receive the praise it deserved. Heyman believes this is due to it needing to be “recognised as independent from English [nonsense] as well as other Indian literary forms”, and its need to be “accepted as a serious Indian art.” (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xl). Differentiating this as a separate genre is challenging especially in the face of such well known English writers as Lear and Carroll. Bengali nonsense has struggled to make it’s mark in the western world in the face of such popular and influential fellow writers.

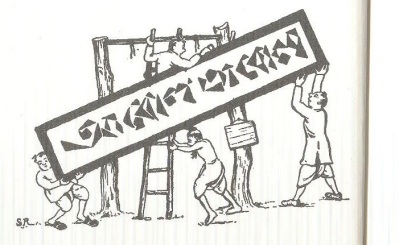

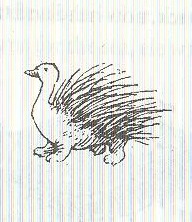

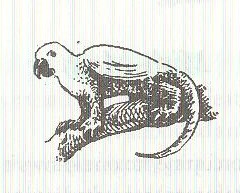

Sukumar Ray is notably one of the most prolific Bengali nonsense writers. This anthology contains three examples from his 1923 works entitled Abol Tabol, along with which he produced his own distinct illustrations, much like Edward Lear. Ray grew up reading the work of Lear and Carroll and this had a massive affect on his own writing style and love of nonsense. Heyman writes that “the influence of the English on Indian nonsense is undeniable” and that it can be mainly seen through the “use of illustration and characterisation”. (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xxxiv) Ray has created likeable characters and provided detailed and amusing illustrations to support his poems, as seen in the poem ‘Mish-Mash’. Like Lear’s illustrations, Ray’s help to develop the plots and characters of his poems and stories in order to achieve the nonsensicality that he aimed for. Heyman notes that Indian nonsense does have it’s distinct differences from English nonsense. He writes that “Indian nonsense places it’s characters close[r] to real Indian life”. (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xxxvii) He goes on to list an “obsession with food”, “large families” and “extreme weather” as all being key features of Indian nonsense. Each of these these are derived from Indian life in particular. As a culture their love of colourful and exotic food is well known, as well as their tendency for large families. Examples of these can be seen in the poems ‘The Old Woman’s Grandma-in-Law’s Five Sisters’ by Rabindranath Tagore and ‘Easy’ by Sampurna Chattarji. Indian weather and nature is also significant due to the countries extreme conditions of extended hot and dry periods followed by torrential rains. The poem ‘Mish-Mash’ is a good example of this use of nature. As well as inherently Indian themes, Indian nonsense can also be distinguished from English nonsense by the highly respectful treatment of their culture. Heyman notes that “aesthetics, politics, religion, class issues, respect for elders and the guru” are all treated with the utmost importance. (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp.xxxix) Indian nonsense poets are often very careful not to offend or disrespect any of these aspects of their culture. For example the poem ‘The Ol’ Crone’s Home’ describes an old woman and her decrepit house. The description is vivid and musical but still respectful of her character. Despite the evident fragility of her and her house Ray emphasises her resilience and strength as she attempts to “prop[s] a stick in vain” in order to prevent her house falling down. Also, his illustration of her character is significant as despite the damaged and “rickety” house around her she still seems to be smiling.

Sukumar Ray established his love of nonsense literature in college where he published his own hand written magazine about humour called “Thirty-two and a Half Fries”.6 Following this he briefly studied in England in 1911 and in 1915 took over the his fathers magazine “Sandesh”. (Ray, ‘Sukumar Ray’) He has notably been influenced by Lear and Carroll as previously mentioned, however he was at the forefront of differentiating Indian nonsense in it’s own right. In Ray’s introduction to his 1923 works Abol Tabol, he claims that “This book was conceived in the spirit of whimsy. It is not meant for those who do not enjoy that spirit.” (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp. xl) This was written in relation to the nine ‘rasas’ which formed the basis of Indian literature till this time. Heyman describes a ‘rasa’ as “an ancient treaties on the arts”. (Heyman, ‘The Tenth Rasa’, pp. Xli) They each correspond to an emotion, for example love or anger, and are how literature was categorised. Sukumar Ray introduced a new ‘rasa’, the “rasa of whimsy”, to differentiate nonsense literature from other forms.

Ray was passionate about nonsense as seen from the examples of his work in this anthology. His poem ‘Gibberish-Gibberish’ explores language and music through the use of alliteration and rhyme. He also toys with nonsense words such as “glusician”. Phonological sounds are significant in Ray’s poems. Ruskin Bond states that “the Bengali language lends itself to rhyme and rhythm, puns and word-play. What Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll did with English, Ray could do with Bengali”. (Bond, ‘Wordygurdyboom!’, pp.xii) ‘Gibberish-Gibberish’ feels almost like a personal welcome from Ray himself in to the world of nonsense. He writes, “come you travellers to the world of babblers” which shows his desire to get readers interested in nonsense poetry. Ray describes nonsense as “mad songs” that cause your mind to “float off like a loon” which perfectly shows his opinion of what nonsense should be; free and full of whimsy. The second Sukumar Ray poem in this anthology is ‘Mish-Mash’, an incredibly imaginative and unique poem that defies all logic and combines completely different animals in order to create a new species such as the “elewhale” and the “duckupine”. The final Sukumar Ray poem is ‘The Ol’ Crone’s Home’. As previously mentioned this poem adheres to the Indian notion of respectfulness, however it evokes powerful images of poverty and age that fit with Heyman’s belief that nonsense literature acts to educate children of the ‘awful’ in life which they have not yet encountered. This social comment on poverty will resonate with both adults and children and acts in contrast to the lives of most readers. This poem uses a couplet rhyming scheme which allows the poem to flow freely.

As this anthology is about Bengali poetry all the poems were originally written in the Bengali language and therefore, as mentioned earlier in this introduction, the problem of language barriers and translation becomes relevant. The translator of all the poems in this anthology was the talented Sampurna Chattarji. She was born in east Africa and has worked as a poet, fiction writer and translator throughout her life. She has translated many Bengali poems and of Ray’s in particular she states that she focused much of her attention on the rhyme and musicality. She attributes the Bengali language as having a “riotous caboodle of effects” that can be used in order to create vibrant nonsense literature. She addresses the particular difficulty with nonsense literature as being the creation of nonsense words that have no logical or easy translation. She says “[I resorted] at times to outrageous word-making, of the kind that could only be excused in a nonsense lexicon”. Here she admits that translating word-for-word is an impossible task when the words do not exist in the original language, let alone any others. So Chattarji used her knowledge of Ray and his style of writing to interpret and create words in English that could mimic the Bengali nonsense words in a similar way, for example through specific rhyming formulations. She also addresses the difficulty of translating puns, as they are usually language and culture specific. She wrote that “a crackling pun in one language is often little more than a damp squib in another.” She goes on to state that her solution to this problem was to re-create the pun in another language in a manner that was as equal as possible in intent. For example she explains that “If the original pun is on a word within a word, then I have tried to find an English counterpart that delivers the same effect.” (Chattarji in ‘Wordygurdyboom!, Translator’s Note) This is not without it’s problems, as obviously language barriers mean and problems with translating nonsense words can lead to an impairment of understanding. However, I believe that that Chattarji’s translations convey Ray’s creativity effectively. The final two poems in this anthology are also by Bengali poets. ‘Easy’ a poem by Chattarji herself is very short and is from her anthology The Food Finagle: A Culinary Caper which centres on the theme of food. The other poem is from the well respected Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore whose poetry was typically meant for children only. ‘The Old Woman’s Grandma-in-Law’s Five Sisters’ shows the common theme of large families. Both Chattarji and Tagore have been included in this anthology of Bengali nonsense poetry as they are other examples that show the imagination and form of Bengali nonsense.

This anthology highlights some of the great Bengali nonsense poets who deserves more recognition for their dedication and submissions to the genre of nonsense literature. Sukumar Ray, in particular, created inventive and truly nonsensical poetry to rival that of fellow writers Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. With the beauty and authenticity of Bengali culture at the heart of his poems he created a window in to a culture that not many get the pleasure to experience. Along with Rabindranath Tagore and the undeniably talented poet and translator Sampurna Chattarji I hope this anthology encourages readers to delve further into the passionate and indulgent Bengali culture and continue to experience nonsense literature from around the world and enjoy all the creative and expressive diversity they behold.

Footnotes:

1. Susan Stewart, Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature (London: The John Hopkins Press Ltd, 1979) pp. vii.

2. Hugh Haughton, The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry (London: Chatto and Windus, 1988) pp.3.

3. Carolyn Wells, Edward Lear Homepage, ‘Introduction to a Nonsense Anthology’ (2012)<http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/pdf/wells_1903.pdf> [accessed 13/03/2015]

4. The Tenth Rasa: An Anthology of Indian Nonsense, ed by Michael Heyman (India: Penguin Books, 2007) pp. xxxv.

5. Sukumar Ray, in Wordygurdyboom! {Abol Tabol} The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray, ed by Ruskin Bond (India: Puffin by penguin Books, 2008) pp. The India Pages.

6. Satyajit Ray, Youtube, ‘SUKUMAR RAY (1987 Documentary)’ (2011) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRg1WbFvXqo> [Accessed 25/05/2015]

Bibliography

Primary Texts:

Ray, Sukumar in Wordygurdyboom! {Abol Tabol} The Nonsense World Of Sukumar Ray, ed. By Ruskin Bond (India: Puffin by Penguin Books, 2008)

The Tenth Rasa: An Anthology of Indian Nonsense, ed. By Michael Heyman (India: Penguin Books 2007)

Secondary Reading:

Haughton, Hugh, The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry (London: Chatto and Windus, 1988)

Ray, Satyajit, Youtube, ‘SUKUMAR RAY (1987 Documentary)’ (2011)<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRg1WbFvXqo> [Accessed 25/05/2015]

Stewart, Susan, Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature (London: The John Hopkins Press Ltd, 1979)

Wells, Carolyn, Edward Lear Homepage, ‘Introduction to a Nonsense Anthology’ (2012) <http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/pdf/wells_1903.pdf> [accessed 13/03/2015]

Anthology

Gibberish-Gibberish by Sukumar Ray. Translated by Sampurna Chattarji

Come happy fool whimsical cool

come dreaming dancing fancy-free,

Come mad musician glad glusician

beating your drum with glee.

Come o come where mad songs are sung

without any meaning or tune,

Come to the place where without a trace

your mind floats off like a loon.

Come scatterbrain up tidy lane

wake, shake and rattle and roll,

Come lawless creatures with wilful features

each unbound and clueless soul.

Nonsensical ways topsy-turvy gaze

stay delirious all the time,

Come you travellers to the world of babblers

and the beat of impossible rhyme.

Mish Mash by Sukumar Ray. Translated by Sampurna Chattarji

A duck and a porcupine, on one knows how,

(Contrary to grammar) are a duckupine now.

The stork told the tortoise, ‘Isn’t this fun!

As the stortoise, we’re second to non!’

The parrot-faced lizard felt rather silly-

Must he give up insects and start eating chilli?

The goat charged the scorpion at a rapid run

jumped on his back, now head and tail are one.

The giraffe lost his taste for roaming far and wide,

like a grasshopper he’d rather jump and glide.

The cow said. ‘Am I sick, too, from this disease?

Or why should the rooster chase me, if you please?’

And oh the poor elewhale – that was a bungle,

while whale yearns for the sea, ele wants the jungle.

The hornbill was desperate as it had no horns,

merged with a deer now, it no longer mourns.

The Ol’ Crone’s Home by Sukumar Ray. Translated by Sampurna Chattarji

Mouthful of puffed rice, smiling and chomping,

In a ricket-rackety house, a clickety crone is stomping.

Bedful of cobbywebs, headful of soot,

Inky-Blinky bleary eyes, back bent like a root.

Pins old the house up, glue sticks it down,

She herself licks the thread that winds all around.

Don’t dare lean too hard or bare boards may break.

Don’t cough hick-hack, the brick-brack will shake.

Plonk goes the streetcart, honk goes the car,

Smash goes the beam, crash the house on to the tar.

Wonky-wobbly are the rooms, holey-moley walls,

Swept with dusty brooms causing musty splinter-falls.

The ceiling gets soggy and saggy in the rain,

The ol’crone all alone props a stick in vain.

Fix it, nix it, day and night a-grouse,

The clickety-clackety crone in her rickety-rackety house.

The Old Woman’s Grandma-in-Law’s Five Sisters by Rabindranath Tagore. Translated by Sampurna Chattarji.

The old woman’s grandma-in-law’s

Five sisters live in a Brick-a-Brac,

Their saris hand upon the stove,

Their pots upon the clothes rack.

Prying fault-finding eyes they fox

By living in a cast-iron box,

For a spot of air their money

They by open windows stack,

And put in every limeless betel leaf

The salt their curries lack.

Easy by Sampurna Chattarji

How can you make an omelette without breaking any eggs?

Easy, fry tomatoes in yellow flour and eat is standing on your legs!