A Nonsense Anthology of Anthropomorphism in Children’s Literature

A Critical Introduction

Anthropomorphism, the “ascription of a human attribute or personality to anything impersonal or irrational”, has been a trope of children’s Literature since the composition of the Aesopica in 600BCE[1]. The Aesopica or as it is more commonly known Aesop’s Fables, is a series in which animals are anthropomorphised and evoke moral lessons such as in the ‘Hare and the Tortoise’. In addition the fables were illustrated so to form text-image cohesion between the anthropomorphised characters and their fable (Fig.1). The evocation of anthropomorphism and didacticism as in Aesop’s Fables continued throughout history and can be seen to have particularly frequented Children’s Literature. For instance 1765 saw the publication of Mother Goose’s Melody, which is a book of playful poetry juxtaposed with maxims such as in ‘Dickery Dickery Dock’ (Fig.2). Burke and Coppenhaver suggest that the use of anthropomorphism in this moralising way is so to “give children pleasure [whilst] they were being instructed”[2]. This is because the use of familiar and lively animals softens the didacticism that to children may be “socially controversial”, allowing them to learn in a imaginative environment. (Burke and Coppenhaver, pp.210). Anthropomorphism therefore becomes a conservative guise for educating children about society and life.

So what does Nonsense Literature have to do with this I hear you ask? Well, Nonsense Literature is a somewhat problematic Genre as its standard definition is “that which is not sense”, and thus what constitutes for one critic as Nonsense can radically differ from another[3]. When devising an Anthology thus, one has the choice to conform to any one interpretation of Nonsense which supports their reading of their respective Nonsense Literature extracts. In this instance the asserted definition is that of Hugh Haughton. In his introduction to the Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry (1988) Haughton describes Nonsense Literature as “in its comic guise, dealing with the serious things of our lives”.[4] Here, Haughton ascribes Nonsense Literature the powerful social purpose of educating the reader about the more serious matters such as “desire, death, identity and authority”; in a similar manner to the function of anthropomorphism as described by Burke and Coppenhaver (Haughton, pp.3). This Anthology therefore explores how Nonsense Literature which contains anthropomorphism functions cross periodically, in educating children about society.

The Victorian Era (1837-1901) is often noted as the birthplace of Nonsense. For instance John Lehmann credits Lewis Caroll and Edward Lear as the forefathers of Nonsense, claiming they are responsible for what was a “popular and so widespread” movement[5]. In 1865 Caroll published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and as Cohen suggests, the book “earned almost unconditional praise”[6]. Behind the novel’s humorous tales that unravel Alice’s navigation through Wonderland, is the social commentary on Victorian society. During the Victorian era there was a great deal of pressure on young children and many were expected to work. Most explicitly however there was pressure on young girls, for instance as Lurie suggests Victorian girls were expected to be “angels of the home” [7]. Carroll however writes Alice as a subversion of this ideal as Alice is shown to be “active, brave and impatient” (Lurie, pp.78). In the novel the anthropomorphism of the White Rabbit can seen to be a representation of Alice’s anxiety about living up to the ideal image of the Victorian child.

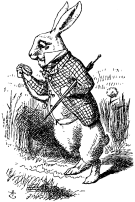

This is emphatically suggested for example when Alice first encounters him (Extract 1.) In the extract this is signified through the Rabbit’s repeated worry that he is “late”: “Oh dear! Oh Dear” I shall be late!” / “Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it is getting!” (Caroll, pp.38). In addition this is shown in his checking of his pocket watch, which is emphasised through the text-image cohesion. The White Rabbit’s hyperbolic repetition of the onomatopoeic “oh”, juxtaposed with the repeated use of exclamation marks “!”, highlights the extent of anxiety the rabbit feels. This becomes nonsensical as the talking rabbit subverts natural order, but also comic as the rabbit’s image juxtaposed with his hyperbolic speech creates a humorous character. Anthropomorphism functions here as Swallow-Prior suggests, through the illustration which emphasises the textual description, as “animals are still animals, but are presented in a way that allows the reader to identify” with them[8]. The rabbit’s image, shown through Tenniel’s illustration (Fig.3) shows he is still an animal through the pastoral setting and animal face, otherwise however the rabbit represents a human as he adopts human posture, height, hands, eyes and clothing. Like Alice the reader is able to take pleasure in the imaginative character of the White Rabbit, but is still able to identify with the animal because of his human attributes. The reader is thus “instructed” on, or is able to at least acknowledge, the issue of anxiety which the Rabbit symbolises (Burke and Coppenhaver, pp.208). Carroll’s use of anthropomorphism here thus educates the reader about the silliness of misplaced anxiety, suggesting that children should be less concerned with defining themselves against hegemonic ideals, and should instead enjoy themselves.

On the other hand the extract can be read as a caution against curiosity. This is because the White Rabbit’s anthropomorphic appearance is what catalyses Alice’s descent into the dangerous and logic defying wonderland. Carroll describes the Rabbit’s appearance as “burning with curiosity” in Alice’s mind (Carroll, pp.38). The use of the diction “burning” evokes a sense of danger, foreshadowing the perils of Wonderland thus suggesting the potential dangers of inquisitiveness. Alice’s interest stems from her initial inability to distinguish herself from the rabbit because they both wear clothes, as she notes that at first it “all seemed quite natural” (Carroll, pp.38). Alice’s curiosity about her identity and what defines her from the animals plays on fears of inter-species confusion, which stemmed from Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859). The novel can consequently be seen as a novel about identity, in which Alice questions who she is/should be in relation to the animals which reside in Wonderland. Alice’s “active [and] brave” journey into Wonderland as a quest for identity subverts the stereotype of the docile Victorian young girl (Lurie, pp.78). The anthropomorphised Rabbit thus becomes a symbol of the dangers of curiosity. The ‘education’ of the child reader comes therefore from Carroll’s presentation of Alice’s choices to subvert Victorian hegemony as potentially threatening and dangerous. This is because the nonsensical world of Wonderland defies logic and order and has many risks. The child thus learns to not be tempted by appearances and curiosity (the anthropomorphic rabbit) and is taught instead to obey the rules of society.

Murphy suggests that ultimately Lear is the “laureate of nonsense” on account of his plethora on Nonsense Literature which resonated throughout the Victorian era, which began with his Book of Nonsense in 1846[9]. Like Carroll, Lear’s work is overwhelmed by the use of anthropomorphism with accompanying illustrations that ultimately seek to ‘educate’ its child audience. Explicitly in his poem Mr and Mrs Spikky Sparrow Lear discusses the importance of ‘fitting in’ in Victorian society, similar to how Alice can be interpreted as cautioning against individuality (Extract 2.). Firstly Lear’s decision to anthropomorphise sparrows is important as in Victorian society Sparrows were seen as the pariah of birds. For instance Russell noted that the Victorians could “do as well without Sparrows as without Rats or Cockroaches”[10]. In the poem the anthropomorphised Sparrows who go to town to dress themselves appropriately represent how children in Victorian society had to respectively adopt social conventions so to not become pariahs. In the poem therefore Lear uses clothing as a symbol of the rules and regulations that children must adapt to, and the children are thus “instructed” on what to do by following the example of the Sparrows (Burke and Coppenhaver pp.208). In the poem Lear reveals the expectations through the Sparrows anthropomorphised conversation as they discuss how Mr Sparrow’s hat-less head is “wrong” because “no one” else does that, and how Mrs Sparrow “ought (…) to wear a bonnet” (Lear, 3.3 / 4.8). The use of the modal auxiliary “ought” shows how Mrs Sparrow is defying what is expected of her, similar to the use of the diction “wrong” to describe Mr Sparrow’s actions. This is emphasised by the implication that “no one” else behaves like that, as it conveys how Mr Sparrow would be considered different and thus how he must learn to adapt. Lear continues this idea when the Sparrows note they must adapt so they are “completely in the fashion” as the use of the adverb “completely” connotes how they must fully adapt to the “fashion” (Lear, 5.1). This is so that the Sparrows’ are wholly accepted by society which will have positive emotional effects by making they feel “quite galloobious and genteel!” (Lear, 5.6). Here, as Applebee suggests “having animals do the active mistake-making allows face saving emotional distance” allowing the reader to identify the issue and then learn through imitation[11].The success of the Sparrow’s is evident at the end of the poem as the baby Sparrow’s note that now “We (…) shall look like other people”, which is emphasised by Lear’s illustration (Lear 7.8) (Fig.4). The anthropomorphic illustration in which the Sparrow’s wear a Bonnet and a Top-Hat symbolises their success in adapting to the rules of society, as the image is one of domestic bliss.

The use of the refrain in the poem, which Bradshaw calls “pure nonsensical language” also aids in the reader’s ‘education’[12]. This is because the continued use of the refrain creates a sense of order reflecting the ordered rules and regulations of society which they must adapt to. This idea is emphasised explicitly through the refrains language which can be seen as an anthropomorphic representation of the language of Sparrows (Lear, 7.9-11):-

‘Witchy witchy witchy wee,

‘Twikky mikky bikky bee,

Zikky sikky tee.’

In this instance therefore the anthropomorphism as Burke and Coppenhaver argue gives children “pleasure” through the use of nonsensical language aided by Lear’s illustration (Burke and Coppenhaver, pp.208). In addition anthropomorphism and nonsense combine to educate the reader showing them how they must behave in order to be successful in society, similar to how Carroll uses Alice to warn against deviating from Victorian hegemony.

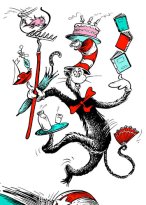

As Scott suggests, “at the top of the juvenile pantheon” for Twentieth Century Children’s Nonsense Literature is, Dr. Seuss[13]. Seuss was originally turned away by publishers as his early work was said to be too progressive and lacking in didacticism which would “transform children into good citizens” (Scott, para.6). During this time America faced political issues as a result of the ‘Red Scare’ and its’ war on Communism, and youth culture was in upheaval taking a stance against the war in political groups such as the ‘Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’. However, in 1957 Seuss successfully published The Cat in The Hat, which can be seen as a book which explores the dichotomy of chaos and order which was rife in 1950’s America (Extract 3.). As Marcus suggests in the book Seuss uses “nonsense as a device for holding the interest of the reader whilst he [says] something important”[14]. In this instance Seuss uses rhyme and a nonsensical narrative so to engage the interest of the reader whilst suggesting the temporality of chaos and necessary consistency of order. As Bader suggest in the book Seuss displays how he is a “natural moraliser” through the anthropomorphism of both the Cat and the Fish, who depict and argue out the divide between chaos and order[15] . In the extract Seuss uses the Cat to symbolise anarchy and chaos as he is disruptive, excessive and demands attention. For instance he demands the children to repeated look at him as he attempts to balance multiple items on himself but inevitably causes chaos by dropping everything (Seuss, 1.1-3 / 2.2-4):-

“look at me!

look at me!

look at me NOW!”

(…)

then he fell on his head!

he came down with a bump.

The encounter is juxtaposed with a colourful illustration which aids in the “comic guise” of the Cat who is shown as laughing whilst performing his tricks (Haughton, pp.2) (Fig.5). Seuss emphasises the Cat as an anthropomorphic symbol of chaos through the creation of the Fish as an anthropomorphic symbol of order and regulation. For instance this is shown following the Cat’s fall (Seuss, 2.):-

‘now look what you did!’

said the fish to the cat.

‘now look at this house!

look at this! look at that!

you sank our toy ship,

sank it deep in the cake.

you shook up our house

and you bent our new rake.

you SHOULD NOT be here

when our mother is not.

you get out of this house!’

said the fish in the pot.

In the extract the Fish resonates as a rule enforcing character who points out the Cat’s wrong doings. This is suggested through the repeated use of “you” and the repeated use of the imperative “look”, which forces the Cat to reflect on the consequences of his chaotic nature. Seuss emphasises this through the use of capitalisation as the Fish tells the cat that he “SHOULD NOT” be there and so must leave (Seuss, 3.9). In this instance the anthropomorphism functions again by “having animals do the active mistake-making”, allowing children to learn from the Cat’s mistakes and acknowledging that chaos causes trouble (Applebee, pp.213). As Scott suggests through the anthropomorphism Seuss allows children to “delight in the liberties of imagination, without condoning anarchy”[16]. This is because the children and reader are able to take “pleasure” in the nonsensical narrative and illustrations, but like Sally and the boy is able to acknowledge that ultimately rules and regulations should be obeyed (Burke and Coppenhaver, pp.208). This is suggested at the end of the novel when Sally and the boy are unable to answer their mother’s question if they had fun or not, and consider lying to her (Seuss, 4):

“And sally and i did not know

What to say.

Should we tell her,

The things that went on there that day?”

Ultimately therefore Seuss connotes to the children of America how they should stray from being chaotic and rebelling against the dominant order.

In 1961 Roald Dahl published James and the Giant Peach. Although Dahl is not typically classed as a nonsense writer many of his books including James, have prominent nonsensical elements and use anthropomorphism to ‘educate’ their readers. Haughton’s definition of as instructing children is evident in Dahl’s work as Held suggests, because “Dahl begins from the fact life is chaotic and often painful” and so subsequently “does not lie to children”[17]. In his work Dahl plays on themes similar to those encountered in this anthology, such as in the case of James, issues of identity. In the book Dahl anthropomorphises insects as representations of children who are in some way ‘different’, and shows how ‘difference’ is a blessing. In James, Dahl shows how both the Centipede and Earthworm are criticised because of their individual characteristics. For example Centipede is told there is “nothing marvellous (…) about having a lot of legs” but responds that Earthworm just cannot see “how splendid” he looks. In addition Earthworm also has to defend himself that he’s “not a slimy beast [but] a useful creature” (Dahl, pp.12). Here Dahl shows through the anthropomorphic characters that people like insects are more than just their stereotypes. In this instance the positive-body image outlook given by the insects instructs the reader to adopt a similar outlook. This is because the anthropomorphism of the insects, aided by the illustrations present the animals in a manner which “allows the reader to identify with the animals experience” (Swallow-Prior, 3.). In this instance the child identifies with ideas of body image and imitates the insect’s positive outlook in the face of diversity, whilst enjoying the humorous drawing of Centipede in his beloved boots (Fig.6).

In addition in the book Centipede’s individuality is also explored through his nonsensical songs (Extract 4.). In the extract Dahl uses “pure nonsensical language”, like Lear in Mr and Mrs Spikky Sparrow, to show the Centipedes unique taste (Bradshaw). For example the Centipede describes having eaten “dandyprats”, “slobbages” and “hot noodles made from poodles” (Dahl, lines 1/6/13). The use of nonsensical language and internal rhyme when Centipede describes his delicacies helps to emphasise Centipedes diversion from the societal understanding of what Centipedes eat. The presentation of this diversion as imaginative and fun, which is suggested by the plays on words in Centipedes nonsensical array of food which transforms sausages(?) to “slobbages”, shows things outside the ordinary in an ameliorative manner. In this case the use of Centipede’s anthropomorphic song juxtaposed with nonsensical language helps the child learn through showing how it is acceptable to have alternate tastes. The child is both “instructed” through Centipedes positive attitude, but also takes “pleasure” in the nonsensical narrative (Burke and Coppenhaver, pp.208).

Finally Dahl shows ‘difference’ as something positive through ‘rewarding’ Centipedes (and the other insects) positive attitude at the end of the book with a job which highlights his individuality (Dahl, pp.72):-

“The Centipede was made Vice-President-in-Charge-of-Sales of a high-class firm of boot and shoe manufacturers.

The Earthworm, with his lovely pink skin, was employed by a company that made women’s face creams to speak commercials on television.”

In the extract therefore anthropomorphism is again utilised to educate children on embracing individuality through the “comic guise” of the insect’s tales (Haughton, pp.2).

This Anthology thus seeks to display the continued practise of the juxtaposition of anthropomorphism and nonsense in Children’s Literature, and how it serves the conservative function of education. The chosen extracts exemplify how this practical juxtaposition functions cross periodically, dealing with the relevant social issues of the milleu, from identity and burgeoning curiosity to diversity. The nonsense texts illuminate however how education does not have to be straightforward, and logical. The extracts which juxtapose anthropomorphism with nonsensical language and illogical worlds illustrate how children can, and do, learn about society through imagination and subversive forms, illustrating the power of Nonsense Literature.

Bibliography

[1] OED, ‘anthropomorphism’, n, 1.b, www.oed.com, [accessed 11/05/15].

[2] Carolyn Burke and Joby Coppenhaver, Animals as People in Children’s Literature, in Language Arts: Explorations of Genre, Volume 81.3, (Urbana: National Council of Readers of English, 2004), pp.208.

[3] OED, ‘nonsense’, n, 1.a, www.oed.com, [accessed 11/05/15].

[4] Hugh Haughton, Introduction, in The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry, ed. Hugh Haughton, (London: Chatto and Windus, 1988), pp.2.

[5] John F. Lehmann, Lewis Carroll and The Spirit of Nonsense, (Nottingham: The University of Nottingham, 1972), pp.34.

[6] Morton N. Cohen, Lewis Carroll: A Biography, (London: Vintage, 1996), pp. 17.

[7] Alison Lurie, Don’t tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children’s Literature, (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1990), pp.78.

[8] Karen Swallow-Prior, Ask the Animals and They Will Teach You, Flourish Magazine Online, (07.2011), < http://www.flourishonline.org/2011/07/lessons-from-literature-about-animals/> , [Accessed 13/05/15], (paragraph 3.).

[9] Ray Murphy, Edward Lear’s Indian Journal, ed. Ray Murphy, (London: Jarrolds, 1953), pp.12.

[10]Colonel. C. Russell, The House Sparrow, (London: Wesley and Son, 1885), pp.21.

[11]Applebee, in Animals as People in Children’s Literature, in Language Arts: Explorations of Genre, ed. Carolyn Burke and Joby Coppenhaver Volume 81.3, (Urbana: National Council of Readers of English, 2004), pp.213.

[12] David Bradshaw, “Wretched Sparrows”: Protectionists, Suffragettes and the Irish, in Literature and Language Journals: Woolf Studies Annual, Volume 20.0, < https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-385822055/wretched-sparrows-protectionists-suffragettes>, [Accessed: 15/05/15], (paragraph 2.).

[13] A. O. Scott, Sense and Nonsense, in The New York Times Magazine Online, (11.2000), http://partners.nytimes.com/library/magazine/home/20001126mag-seuss.html , [Accessed: 16/05/15], (paragraph 2.).

[14] Leonard Marcus, in Sense and Nonsense, in The New York Times Magazine Online, ed. A.O. Scott, (11.2000), http://partners.nytimes.com/library/magazine/home/20001126mag-seuss.html , [Accessed 16/05/15], (paragraph 7.).

[15] Barbara Bader, in Sense and Nonsense, in The New York Times Magazine Online, ed. A.O. Scott, (11.2000), http://partners.nytimes.com/library/magazine/home/20001126mag-seuss.html , [Accessed 16/05/15], (paragraph 7.).

[16] A. O. Scott, Sense and Nonsense, in The New York Times Magazine Online, (11.2000), http://partners.nytimes.com/library/magazine/home/20001126mag-seuss.html , [Accessed: 16/05/15], (paragraph 8.)

[17] Jacob M. Held, Roald Dahl and Philosophy: A Little Nonsense Now and Then, (London: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2014), pp. 4.

Appendix

Appendix

(Fig.1)

(Fig.2)

(Fig.3)

(Fig. 4)

(Fig.5)

(Fig.6)

(Extract 1.) Lewis Carroll, Chapter 1: Down the Rabbit Hole, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass, ed. Michael Iwrin, (London: Wordsworth Classics, 2001), pp.38.

“when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her. There was nothing so very remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so very much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, `Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!’ (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat–pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it (…)There was not a moment to be lost: away went Alice like the wind, and was just in time to hear it say, as it turned a corner, `Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it’s getting!’”

(Extract 2.) Edward Lear, Mr and Mrs Spikky Sparrow, in Nonsense Songs, Stories and Botany, (1871), http://www.nonsenselit.org/Lear/ns/sparrow.html , [Accessed: 03/05/15].

|

On a little piece of wood, |

| Mrs. Spikky Sparrow said, ‘Spikky, Darling! in my head ‘Many thoughts of trouble come, ‘Like to flies upon a plum! ‘All last night, among the trees, ‘I heard you cough, I heard you sneeze; ‘And, thought I, it’s come to that ‘Because he does not wear a hat! ‘Chippy wippy sikky tee! ‘Bikky wikky tikky mee! ‘Spikky chippy wee! |

| ‘Not that you are growing old, ‘But the nights are growing cold. ‘No one stays out all night long ‘Without a hat: I’m sure it’s wrong!’ Mr. Spikky said ‘How kind, ‘Dear! you are, to speak your mind! ‘All your life I wish you luck! ‘You are! you are! a lovely duck! ‘Witchy witchy witchy wee! ‘Twitchy witchy witchy bee! Tikky tikky tee! |

| ‘I was also sad, and thinking, ‘When one day I saw you winking, ‘And I heard you sniffle-snuffle, ‘And I saw your feathers ruffle; ‘To myself I sadly said, ‘She’s neuralgia in her head! ‘That dear head has nothing on it! ‘Ought she not to wear a bonnet? ‘Witchy kitchy kitchy wee? ‘Spikky wikky mikky bee? ‘Chippy wippy chee? |

| ‘Let us both fly up to town! ‘There I’ll buy you such a gown! ‘Which, completely in the fashion, ‘You shall tie a sky-blue sash on. ‘And a pair of slippers neat, ‘To fit your darling little feet, ‘So that you will look and feel, ‘Quite galloobious and genteel! ‘Jikky wikky bikky see, ‘Chicky bikky wikky bee, ‘Twikky witchy wee!’ |

| So they both to London went, Alighting on the Monument, Whence they flew down swiftly — pop, Into Moses’ wholesale shop; There they bought a hat and bonnet, And a gown with spots upon it, A satin sash of Cloxam blue, And a pair of slippers too. Zikky wikky mikky bee, Witchy witchy mitchy kee, Sikky tikky wee. |

| Then when so completely drest, Back they flew and reached their nest. Their children cried, ‘O Ma and Pa! ‘How truly beautiful you are!’ Said they, ‘We trust that cold or pain ‘We shall never feel again! ‘While, perched on tree, or house, or steeple, ‘We now shall look like other people. ‘Witchy witchy witchy wee, ‘Twikky mikky bikky bee, Zikky sikky tee.’ |

(Extract 3.) Dr Seuss, The Cat in The Hat, (London: Harper Collins Children’s Books, 2004), pp.21. ‘look at me!look at me!look at me NOW!it is fun to have funbut you have to know how.i can hold up the cupand the milk and the cake!i can hold up these books!and the fish on a rake!i can hold the toy shipand a little toy man!and look! with my taili can hold a red fan!i can fan with the fanas i hop on the ball!but that is not all.oh, no.that is not all…’ that is what the cat said…then he fell on his head!he came down with a bumpfrom up there on the ball.and sally and i,we saw ALL the things fall! and our fish came down, too.he fell into a pot!he said, ‘do i like this?oh, no! i do not.this is not a good game,’said our fish as he lit.’no, i do not like it,not one little bit!’ ‘now look what you did!’said the fish to the cat.’now look at this house!look at this! look at that!you sank our toy ship,sank it deep in the cake.you shook up our houseand you bent our new rake.you SHOULD NOT be herewhen our mother is not.you get out of this house!’said the fish in the pot.(…) “and sally and i did not knowwhat to say.should we tell herthe things that went on there that day?

(Extract 4.) Roald Dahl, The Earthworm, in James and The Giant Peach, http://english4success.ru/Upload/books/449.pdf, [Accessed: 09/05/15], pp.30-31.

“I’ve eaten many strange and scrumptious dishes in my time, Like jellied gnats and dandyprats and earwigs cooked in slime, And mice with rice – – they’re really nice When roasted in their prime. (But don’t forget to sprinkle them with just a pinch of grime.) “I’ve eaten fresh mudburgers by the greatest cooks there are, And scrambled dregs and stinkbugs’ eggs and hornets stewed in tar, And pails of snails and lizards’ tails, And beetles by the jar. (A beetle is improved by just a splash of vinegar.) “I often eat boiled slobbages. They’re grand when served beside Minced doodlebugs and curried slugs. And have you ever tried Mosquitoes’ toes and wampfish roes Most delicately fried? (The only trouble is they disagree with my inside.) “I’m mad for crispy wasp-stings on a piece of buttered toast, And pickled spines of porcupines. And then a gorgeous roast Of dragon’s flesh, well hung, not fresh – – It costs a buck at most, (And comes to you in barrels if you order it by post.) “I crave the tasty tentacles of octopi for tea I like hot-dogs, I LOVE hot-frogs, and surely you’ll agree A plate of soil with engine oil’s A super recipe. (I hardly need to mention that it’s practically free.) “For dinner on my birthday shall I tell you what I chose: Hot noodles made from poodles on a slice of garden hose – – And a rather smelly jelly Made of armadillo’s toes. (The jelly is delicious, but you have to hold your nose.) “Now comes,” the Centipede declared, “the burden of my speech: These foods are rare beyond compare – – some are right out of reach; But there’s no doubt I’d go without A million plates of each For one small mite, One tiny bite Of this FANTASTIC PEACH! “