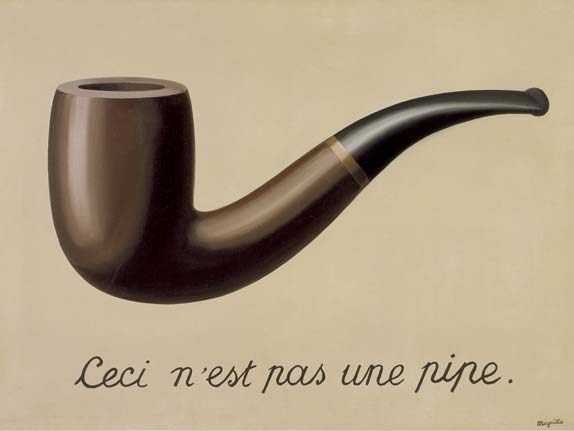

Food is a motif that occurs frequently within the genre of nonsense literature, and is particularly prevalent within the works of canonical nonsense writers such as Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, who are considered to be the founding fathers of the genre. However, since this is an emerging area of literary study, there is much debate amongst academics regarding what constitutes a definition of nonsense. Therefore, a universal definition of the term nonsense is not available, but instead it is open to interpretation. Terry Eagleton has argued that: ‘if there is one sure thing about food, it is that it is never just food. Like the post-structuralist text, food is endlessly interpretable, as gift, threat, poison, recompense, barter, seduction, solidarity, suffocation.’[1] In order to explore the theme of food within nonsense texts, this anthology will focus on Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, two of Edward Lear’s limericks, Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and finally the banquet scene from Guillermo del Toro’s Pans Labyrinth. Within the aforementioned texts the reference to food can be interpreted in a variety of ways, so therefore is in-keeping with Eagleton’s statement. Since nonsense texts tend to be difficult to comprehend (one of the common definitions of nonsense is that it ‘defies sense’[2]), nonsense is arguably ‘endlessly interpretable’, just like Eagleton states that food is. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why food in particular lends itself to this genre. Food plays a fundamental part in everybody’s everyday life so is inextricably linked to notions of class and cultural rituals, as well as often having erotic or religious connotations. Like Alice, many of us take a ‘great interest in questions of eating and drinking.’[3]

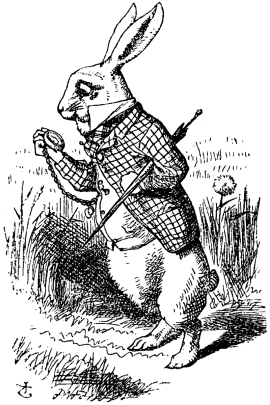

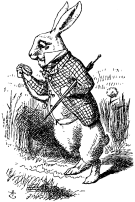

Firstly, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, references to food are made towards the end of the opening chapter, in one of the novel’s most iconic scenes. After shrinking due to drinking a bottle labelled ‘DRINK ME’ (p. 13), Alice discovers ‘a very small cake, on which the words EAT ME were beautifully marked in currants’ (p. 14.) I think that Carroll intentionally selected an item of food which is evocative of the heroine, which possesses feminine traits. As a young girl Alice should be ‘small’, sweet and pretty, the latter of which can be linked to the cake’s aesthetically pleasing presentation. It is also significant that Carroll selected an item of food which is considered to be a treat, rather than an everyday staple such as bread, thus adding to the temptation. Since a cake is a luxury food item, and due to the decorative nature of this particular cake, it is a type of food one would associate with the middle class, which reflects Alice’s identity. As Hugh Haughton states in the introduction to the novel: ‘the fictional Alice measures herself by her superior knowledge and social status’ (p. xli.) Although Alice encounters an identity crisis throughout the novel, her dress and speech suggest her (at the very least) middle class social status.

Additionally, the language used in ‘EAT ME’ (p. 14) is performative, and Alice conforms to this command, which is reminiscent of advertising ploys used to persuade potential consumers to purchase food. Alice’s hunger is not mentioned, but rather she is eating because she has been instructed to do so by the narrator, and is therefore being controlled by Carroll as opposed to acting with agency at this point in the novel. In this chapter the heroine is presented as a consumer. Within the concluding sentence ‘she set to work and soon finished off the cake’ (p. 15), the use of ‘work’ makes eating appear like a task, or something which she is forced to do, whilst the inclusion of ‘anxiously’ (p. 15) in the previous paragraph further stresses that this is not a pleasant process, but on the contrary is laborious. Lisa Coar argues that: ‘it would appear, at times, that Carroll forces Alice to eat in order to feed his own hedonistic hunger for imposing patriarchal punishment on greedy little girls.’[4] Perhaps Carroll intended that Alice’s extreme growth be considered a type of disfigurement, or a source of shame, in order to dissuade her from needlessly consuming calorific food. This would be in-keeping with the attitude towards food and females in Carroll’s era, because ‘in Victorian society, food and femininity were linked in such a way as to promote restrictive eating among privileged adolescent women.’[5] Ideally, girls were expected to have small appetites, and consumption of food to excess was perceived to be an unfeminine trait.

Also, Alice says: ‘she was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size: to be sure, this generally happens when one eats cake, but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way’ (p. 15.) This emphasises that the happenings in Wonderland are peculiar, thus drawing attention to the fact that this text belongs in the genre of nonsense literature, and also shows how Carroll is subverting the conventions of the real. Although this extract does not mention Alice’s enormous increase in size, the beginning of the following chapter describes this. The fact that the consumption of the cake causes Alice’s growth is interesting, because although consumption of food is necessary in order for a child to grow, Carroll has taken this concept and exaggerated Alice’s growth dramatically, thus taking it into the realm of the absurd. This is in-keeping with the characteristics often associated with the nonsense genre. Haight asserts that absurdity is a keynote of nonsense as a literary form, [6] and Alice’s extreme fluctuations in size are certainly absurd.

Moreover, Alice’s physical growth due to the consumption of the cake can be viewed as a metaphor for her emotional growth. Alice develops significantly throughout the book, and I believe that her shrinking and growing in size represents how the process of growing up is not linear, and that on certain days you may feel more mature than others. Alice’s appetite may also represent her sexual desire; throughout the novel Alice is constantly consuming, yet her hunger never seems to be satiated. This suggests it is not food which she requires in order to satisfy her voracious appetite, but rather it is her sexual appetite that needs to be fulfilled. Since Alice is about the beginning stages of the protagonist’s development into womanhood, in addition to belonging to the genre of nonsense literature, it could also be classed as a bildungsroman.

A substantial number of Lear’s limericks in A Book Of Nonsense deal with the subject of food. Although food is not always depicted negatively in his limericks (for example, in certain limericks food acts as a remedy), the extracts I have selected are concerned with the dangers of food when taken to the extreme. In the ‘Old Man of Calcutta’, food is consumed in excess, because Lear writes that the old man ‘perpetually ate bread and butter (line 2.)’[7] This in itself is nonsensical, because the concept of somebody constantly consuming bread and butter is an impossibility. Moreover the concluding two lines ‘till a great bit of muffin, on which he was stuffing/Choked that old man of Calcutta’ (lines 3-4), contradict the previous lines, because a muffin is not bread and butter. This can be associated with religion, because within the Christian tradition gluttony is considered to be one of the seven deadly sins. In the Bible it is warned that those who are gluttonous will suffer the repercussions: ‘for the drunkard and the glutton will come to poverty, and drowsiness will clothe them with rags’ (Prov. 23.21.) It was generally considered that by consuming excessive amounts of food, you take away resources from those in need of food, who will go hungry whilst others grow fat. There is a clear moral message, or warning in Lear’s limerick, which is not to be greedy. The protagonist is given the worst form of punishment for his excessive eating: death. The use of the pejorative adjective ‘horrid’ (line 4) suggests that there may be a link between overconsumption and immorality, because his overeating is the only information we are given about the old man, so we cannot assume any other reason for him being described as ‘horrid’ (line 4.) Moreover, Lear’s accompanying illustration showcases the enormous size of the food that the old man is consuming, as well as his obese form. Also, the old man’s extravagant clothing (the buttoned waistcoat, shirt and smart trousers), indicate that he is wealthy, thus suggesting that there is a correlation between excessive consumption and the higher classes, which links back to the earlier discussion of class in Alice.

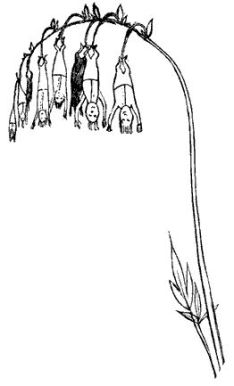

However, as previously stated, Lear is not criticising food itself; another of his limericks is concerned with the perils of not eating enough. ‘The Old Man of Berlin’[8] has a form that is ‘uncommonly thin’ (p. 77), which the accompanying picture illustrates. It depicts a long, narrow, fragile looking man, who, due to his small size, gets ‘mixed up in a cake/ So they baked that old man of Berlin’ (lines 3-4.) This concept is absurd, and the illustration exemplifies the absurdity, because the man, although narrow is still of such a size that the bakers would notice him entering the cake mixture. Moreover, it is ludicrous that the old man has his mouth open during this process, so presumably could have shouted in protest about the impending prospect of him being baked alive. The image also reinforces gender stereotypes about cooking because it is three women who are baking the cake, so suggests that a woman’s role is within the domestic sphere, which is in-keeping with the patriarchal society of Lear’s era. However, conventional notions of gender and power are subverted here, because the female bakers cause the death of the old man.

It is the events in Lear’s limericks which tend to be nonsensical, rather than the incorporation of nonsensical language such as portmanteau words or neologisms, although he does occasionally use words which do not make sense in the given context. Although on the surface this is a comical limerick, it carries alongside it the serious message that not eating enough can cause death. Ideally, with respect to eating, one should find a balance between the ‘Old man of Calcutta’ and ‘the Old man of Berlin.’ The ‘old man’ features frequently throughout Lear’s limericks, and since children are his target audience it adds to the humour that they are reading about the eccentricities of adults, who are supposed to be mature and sensible.

Although Pan’s Labyrinth is much darker than Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, both contain fairy tale like elements, and there are numerous parallels between the two heroines Ofelia and Alice. Both Alice and Ofelia are young girls who enter a subterranean world and embark upon a journey of self-development, encountering strange animals or creatures along their way. I believe that due to the multiple similarities between Pans Labyrinth and Alice (which is a canonical piece of nonsense literature), combined with the fantastical underworld that Ofelia explores, which defies logic with its magical nature, means that this film can be classed as nonsense. Before the second task, Ofelia is instructed ‘not to eat or drink anything during her stay.’[9] This has Biblical allusions to Genesis and the Garden of Eden, where Eve is told not to eat the forbidden fruit. Just as Eve succumbs to temptation and eats the apple, Ofelia eats a grape from the banquet, despite the fact that the fairies actively attempt to prevent her from doing so. As in Eve’s case, whose consumption of the apple leads to the fall of man, so too does Ofelia’s act of disobedience have disastrous consequences. After consuming a grape, the monstrous pale man is awakened. As punishment for Ofelia devouring two of his grapes, the pale man consumes two fairies, in a scene which evokes Francisco Goya’s painting entitled ‘Saturn Devouring His Son.’[10] The death of the fairies is significant, because it could symbolise an attempt to end Ofelia’s obsession with reading fairy tales; at the beginning of the film Ofelia’s mother tells her ‘you’re a bit too old to be filling your head with such nonsense’ (3 minutes 28 seconds.) This is an example of how some people perceive the definition of nonsense to be pejorative, an insult even. Dryden goes so far as to argue that ‘the realms of nonsense are the dumping grounds for literary failures’ (Hugh Haughton Introduction p. 4), which seems peculiar now considering the popularity of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 150 years after its publication.

Not only does the food in the food in this scene relate to religion, but it can also be linked to issues of class and fascism. Pans Labyrinth is set during the Spanish Civil War, which was a time during which the poor were starving and food had to be rationed. The pale man’s table is laden with a huge assortment of luxurious, fresh food items such as meat, fruit, cakes and wine; it is a feast. Although alluring to the hungry Ofelia, the fact that all items of food are differing shades of red is ominous, because it pre-empts the blood that is about to be spilled. This scene mirrors the dinner scene in the ‘real’ world which comes directly before it. The pale man is sat at the head of the table, just as Captain Vidal is, which is suggestive of his monstrous nature. Indulging in a banquet and hoarding food whilst the poor are starving is indicative of Vidal’s cruel, selfish nature. Connections can be seen here with Lear’s ‘Old Man of Calcutta’ limerick, because both that and Pans Labyrinth deal with the theme of greed, and in both cases the consumption of excess food is associated with negative character traits.

Finally, within Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin Market’[11] food plays a pivotal role, and it is the consumption of the goblin men’s fruit which is the catalyst for the traumatic events that occur throughout this narrative poem. The use of ‘Come buy our orchard fruits’ (line 3) can be linked to the performative ‘EAT ME’ (p. 14) in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. ‘Come buy’ is repeated twice in the fourth line and this persuasive language, as in Alice can be likened to advertisement and a consumer culture. Food is seen as a commodity, and the goblins use appealing adjectives in order to entice the maids to purchase their goods. For example, the goblins employ phrases such as ‘plump unpeck’d cherries’ (line 7) and ‘pomegranates full and fine’ (line 21.) The language used to describe the fruit is highly sensual, such as ‘plump’ (line 7) and ‘full and fine’ (line 21), with the suggestive shapes evoking images of the female body. ‘Peaches’ (line 9) have a fleshy texture, ‘cherries’ (line 7) are often used to symbolise virginity whilst ‘unpeck’d’ (line 7) emphasises purity and ‘ripe’ (line 15) has sexual undertones, suggesting a woman’s sexual maturity. The line ‘taste them and try’ (line 25), especially when coupled with ‘figs to fill your mouth’ (line 28), could be interpreted as having sexual connotations, perhaps alluding to oral sex, whilst the juices of the fruit may symbolise bodily fluids. When uttering the latter phrase aloud, the vowels mean it is necessary to open your mouth into an ‘o’ shape, which mimics the action required to consume the fruit. Eating and sex are activities which share similarities: they are both fundamental to survival, can both be pleasurable and engage the same senses of sight, taste and touch. The lines ‘sweet to tongue and sound to eye’ (line 30), explicitly appeal to the senses of sight and taste, whilst the carefully constructed sonic quality of the poem appeals to the ear. The alliterative quality coupled with sibilance, and the arrangement of spondees and trochees makes the goblin’s words themselves have a sensual quality.

Contemporary readers would perhaps gain more pleasure from this list, because it contains a plentiful variety of exotic fruits, and as Victor Roman Mendoza notes, ‘1859 proved a particularly low-yield year for fruit harvesting in England, and so “fresh fruit would indeed have been largely the stuff of fantasy.”[12] There are similarities between fantasy and nonsense, because both are distinctly separated from the real. Examining the topic of nonsense further, Margaret Reynold writes: ‘If the semiotic is ‘the nonsense woven indistinguishably into sense’, then Rossetti’s nonsense story makes sense and the surface-sense of her best-loved poems may be nonsense.’[13] I believe that the latter part of this is an apt description of Goblin Market, because although one could take the poem at face value as being merely about a girl who consumes fruit, I think that such a reading disregards the true ‘sense’ of the poem. Without delving deeper into the symbolism of the fruit, the poem makes little sense because there is no justification for the poem’s narrative events.

In conclusion, the introduction to this anthology explores some of the various ways in which nonsense texts employ food as a motif. Since the nonsense texts discussed (aside from Pan’s Labyrinth) have been written primarily with the intended audience of children, the numerous references to food is understandable, because it is something which all children can relate to, as it forms a part of their everyday routine. As we have discovered throughout this exploration, food is laden with symbolism, and can be considered in relation to sex, religion, class and consumerism, amongst others. Even within a single text, the trope of food can be interpreted in numerous ways. For instance, within the extract from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, food can be viewed in terms of sexual desire, class and as a commodity. Intertwined amongst the analysis of food are references to possible ways in which to define nonsense, and some of its common characteristics. However, the purpose of this introduction to the anthology of nonsense texts is not to reach a definitive conclusion with respect to what constitutes nonsense, but rather to analyse the role of food within nonsense texts, and inspire the reader to consider whether they would classify the selected texts as belonging to the genre of nonsense.

[1] Sarah Shieff, ‘Katherine Mansfield’s Fairytale Food’, Journal of New Zealand Literature, 32.2, (2014), 68-84 (p. 68).

[2] Hugh Haughton, The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry ([n.p.]: Chatto and Windus, 1988), p.2.

[3] Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, ed. by Hugh Haughton (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2009), p. 23.

[4] Lisa Coar, ‘Sugar and Spice and All Things Nice: The Victorian Woman’s All-Consuming Predicament’, Victorian Network, 4.1, (2012), 48-72 (p. 57).

[5] Carole Couniha, Penny van Esterik, Food and Culture: A Reader (New York: Routledge, 1997), p. 168.

[6] M.R Haight, ‘Nonsense’, Brit J of Aesthetics, 11.3, (1971), 247-256 (p. 247).

[7] Edward Lear, The Complete Nonsense and Other Verse, ed. by Vivien Noakes (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2001), p. 74.

[8] Edward Lear, The Complete Book of Nonsense and Other Verse, p. 77.

[9] ‘Pans Labyrinth’, dir. by Guillermo del Toro (Warner Bros, 2006), 56 minutes, 23 seconds.

[10] Figure 1

[11] Christina Rossetti, ‘Goblin Market’, Poetry Foundation, (2015) <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174262> [accessed 10 January 2016] (para 1. of 29

[12] Victor Roman Mendoza, “Come buy’: The Crossing of Sexual and Consumer Desire in Rossetti’s Goblin Market’, ELH, 2006 Winter, 73.4, (2006), 913-47 (p. 923).

[13] Margaret Reynolds, ‘Speaking un-likeness: The double text in Christina Rossetti’s ‘After Death’ and ‘Remember’’, Textual Practice, 13.1, (2012), 25-41 (p. 35).

Bibliography

Primary

Carroll, Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, ed. by Hugh Haughton (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2009)

Lear, Edward, The Complete Nonsense and Other Verse, ed. by Vivien Noakes (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2001)

‘Pans Labyrinth’, dir. by Guillermo del Toro (Warner Bros, 2006)

Rossetti, Christina, ‘Goblin Market’, Poetry Foundation, (2015) <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174262> [accessed 10 January 2016]

Secondary

Coar, Lisa, ‘Sugar and Spice and All Things Nice: The Victorian Woman’s All-Consuming Predicament’, Victorian Network, 4.1, (2012), 48-72

Couniha, Carole and Esterik, Penny, Food and Culture: A Reader (New York: Routledge, 1997)

Haight, M.R, ‘Nonsense’, Brit J of Aesthetics, 11.3, (1971), 247-256

Haughton, Hugh, The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry ([n.p.]: Chatto and Windus, 1988)

Mendoza, Victor, “Come buy’: The Crossing of Sexual and Consumer Desire in Rossetti’s Goblin Market’, ELH, 2006 Winter, 73.4, (2006), 913-47

Reynolds, Margaret, ‘Speaking un-likeness: The double text in Christina Rossetti’s ‘After Death’ and ‘Remember’’, Textual Practice, 13.1, (2012), 25-41

Shieff, Sarah, ‘Katherine Mansfield’s Fairytale Food’, Journal of New Zealand Literature, 32.2, (2014), 68-84

Nonsense Anthology Extracts

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, ed. by Hugh Haughton (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2009), pp. 14-15.

Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words `EAT ME’ were beautifully marked in currants. `Well, I’ll eat it,’ said Alice, `and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door; so either way I’ll get into the garden, and I don’t care which happens!’

She ate a little bit, and said anxiously to herself, `Which way? Which way?’, holding her hand on the top of her head to feel which way it was growing, and she was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size: to be sure, this generally happens when one eats cake, but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way.

So she set to work, and very soon finished off the cake.

Edward Lear, The Complete Nonsense and Other Verse, p. 77.

‘There was an Old Man of Calcutta,

Who perpetually ate bread and butter;

Till a great bit of muffin, on which he was stuffing,

Choked that horrid Old Man of Calcutta.’

Edward Lear, The Complete Nonsense and Other Verse, p. 74.

‘There was an Old Man of Berlin,

Whose form was uncommonly thin;

Till he once, by mistake, was mixed up in a cake,

So they baked that Old Man of Berlin.’

The banquet scene, ‘Pans Labyrinth’, dir. by Guillermo del Toro (Warner Bros, 2006), 56 minutes-62 minutes, 21 seconds.

Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin Market’, Poetry Foundation, (2015) <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174262> [accessed 10 January 2016] (para 1. of 29)

Morning and evening

Maids heard the goblins cry:

“Come buy our orchard fruits,

Come buy, come buy:

Apples and quinces,

Lemons and oranges,

Plump unpeck’d cherries,

Melons and raspberries,

Bloom-down-cheek’d peaches,

Swart-headed mulberries,

Wild free-born cranberries,

Crab-apples, dewberries,

Pine-apples, blackberries,

Apricots, strawberries;—

All ripe together

In summer weather,—

Morns that pass by,

Fair eves that fly;

Come buy, come buy:

Our grapes fresh from the vine,

Pomegranates full and fine,

Dates and sharp bullaces,

Rare pears and greengages,

Damsons and bilberries,

Taste them and try:

Currants and gooseberries,

Bright-fire-like barberries,

Figs to fill your mouth,

Citrons from the South,

Sweet to tongue and sound to eye;

Come buy, come buy.”

Appendix

Figure 1

Francisco Goya, ‘Saturn Devouring His Son’, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art <http://www.19thcenturyart-facos.com/artwork/saturn-devouring-his-children> [accessed 12 January 2016]