If traditional nonsense plays with the unexpected disorder of the universe Surrealism makes a much more serious attempt to economize it. Surrealism seeks an epistemological identity through the marriage of conscious and unconscious realities. By inhabiting the ‘underground’ both Surrealism and nonsense occupy a vertiginous place in time and space. The liminal consciousness of the subject, revered in Surrealism, is a much more troubled concept in nonsense literature. Although parallels can be drawn between the two styles nonsense does not share the Surrealist confidence of subjective ‘transcendence,’ explicitly the reintegration of man and nature, subject and object and conscious and unconscious.

Lewis Carroll’s canonical text of nonsense Alice in Wonderland was valorized by the Surrealists. Alice was a natural muse for the movement’s epistemophilia; her characteristic curiosity, primordial drives and a particular dissatisfaction for arbitrary rules were beguiling to the Surrealist travail. Louis Aragon treats Alice as a symbol of an endemically feminine curiosity; “at an epoch when, in the definitively United Kingdom, all thought was considered so shocking that it might well have hesitated to form itself, what had become of human liberty? It rested in its entirety within the frail hands of Alice.”[1] Thus the nonsense of Carroll’s text is given a specifically political agenda. From its marginal position Alice’s curiosity stands to destabilize specifically patriarchal order. Through the iconography of Pandora and the biblical figure of Eve, Mulvey argues that the myth of female curiosity projects itself “onto and into…forbidden space,”[2] or for Alice, Wonderland. Woman’s invasion of this undetermined territory carries “connotations of transgression and danger” due to her “drive to investigate and uncover secrets.”[3] Thus curiosity is often dismissed as madness or nonsense. For the Surrealists I would argue that this sense of danger manifests itself in an ambiguously conscious othering of woman. The perceived danger of feminine curiosity manifests itself in the reification of hysteria by the Surrealists as “women hysterics are endowed with particularly poetic powers because of that state of Otherness.”[4] The Surrealist ideal of aesthetic madness, feminine irrationality and it’s access to the dream world has a natural alignment to Alice’s Wonderland of nonsense. For the Surrealists Wonderland is a space of this unconscious aesthetic madness, navigated by Alice, a muse of feminine curiosity.

Alice’s fall, unlike Eve’s, is a leisurely and absurdly blithe experience. Having “plenty of time…to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next”[5] Alice surpasses geographical, temporal and rational boundaries. Beer highlights the nonsensical behavior of this space; “wells, however deep, do not usually affect the speed of falling.”[6] Gravity is particularly inconsistent, as Alice falls, the jar of marmalade retains its ‘normal’ weight and she seems to fall faster than numerous cupboards. Alice’s perception of her fall has a vertiginous resonance; “down, down, down” to a place where farcically “people walk with their heads downward.” Avant-garde tendency towards the perception of space and time correlates to the Surrealist agenda. A subject that “is disposed of its privilege” of space must then imperatively experience a displaced reality. Whilst in Surrealism this is a frankly violent displacement, Alice seems to take the nonsense in her stride, maintaining a specifically Victorian politeness – “fancy curtseying as you’re falling through the air!”

Whilst Surrealism privileges an authenticity surrounding the violent displacement of the subject, nonsense commits to neither reality nor non-reality. Instead nonsense problematizes natural as well as nonsensical laws. This is particularly evident in the corporality of Carroll’s world. The immaterial dreamscape of Wonderland comes to life with a resounding “thump! thump!” The tangibility of the onomatopoeic sound transcends the sensory boundaries; we can almost ‘hear’ Alice land as we read the text. The word materializes abstract experience and so Carroll’s written word becomes both visual and aural. Nonsense consistently pushes the boundaries of language. The orthodoxy of language as a privileged medium and the tension between language and reality manifests in ceaseless subversion of language in Surrealism. This approach undoubtedly draws its roots from Dadaism (of which Surrealism was descendent), which assaulted the notion of hierarchical language systems.

The arbitrariness of language is illustrated by Alice’s hypnagogic question– “do cats eat bats…do bats eat cats.” Through its inversion the sentence becomes a linguistic paradox; the terms are undoubtedly a minimal pair but as Lecercle points out “the context is so peculiar that it prevents the normal application of [grammatical] rules.”[7] Alice states, “As she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it” thus the meaning of both words becomes identical, phonetically /k/ and /b/ are interchangeable. Lecercle proposes that this conscious negation of the rules of grammar shows that “the attitude of nonsense texts towards language is not one of playful imitation and random disorganization.”[8] Nonsense thus shares the Surrealist propensity for the “simultaneous creation and negation”[9] of the system of language.

The allegory of Alice’s fall also maps closely onto a decent into the Freudian unconscious. Arguably to produce nonsense in the face of reality is a rational response. According to Freud the “inner nature is just as imperfectly reported to us through the data of consciousness as is the external world through the indications of our sensory organs.”[10] The disorientation of the subject that often occurs in nonsense and Surrealist texts thus imagines this discrepancy. Where Carroll cautiously approaches the tension between the conscious and the unconscious, the subject is enthusiastically taken up by Surrealism, which seeks “both physical and metaphysical satisfaction by pushing back the frontiers of logical reality.” The uncertainty of subjectivity manifests in Alice’s insatiable curiosity, however resolution to her quest for knowledge is presented as dangerous in the text. Alice’s curiosity is boundless in a specifically modal and temporally uncertain linguistic space; as she consistently uses the modal verbs “shall,” “must,” and “hope” her questions are voiced in future tense “it will never do to ask.” However a change occurs as Alice is at the threshold of consciousness and demands “now, Dinah, tell me the truth.” This imperative is followed by Alice’s violent arrival in Wonderland as “suddenly…the fall was over.” Her conviction is interrupted thus the reader is in left in an ambiguously liminal reality where truth is erratic. Carroll’s refusal to designate reliable space feeds into Surrealist dismissal of the confines of ‘order,’ as Aragon states, “the idea of the limit is the only inconceivable idea.”

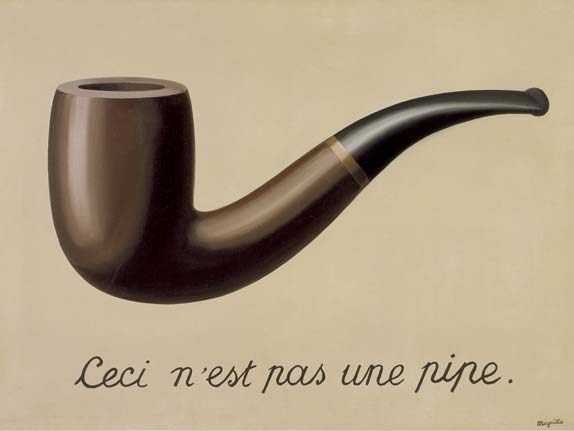

The idea of the limit is semiotically interrogated in both Surrealism and nonsense literature. The interaction between text and image, present in nonsense literature, is consciously and critically examined in Surrealist art. Magritte’s famous work The Treachery of Images[11] exposes many of the antagonisms of representation. Nonsense literature’s affinity for text and image, as in the works of both Carroll and Lear, is significant when we consider that the structure and rules of semiotic interpretation are looser than that of grammar and syntax. Nonsense as a genre already pushes the boundaries of linguistic decorum and then complicates this by adding another layer of interpretation through image. For nonsense literature the use of pictures that accompany the text is another way of expanding the boundaries of the written word. In Magritte’s work nevertheless the interaction of text and image is more violent, though not less pleasurable. The painting depicts a pipe under which the sentence “ceci n’est pas une pipe” is written. When the two interact, the natural polysemy of images lends a stronger reliance on the text to anchor meaning. As the two act upon each other in an interpretive relay the boundary between the two modes of representation becomes unconvincing. Where the viewer seeks confidence in their interpretation of the image Magritte undermines this with an oxymoron. Both text and image thus perpetually undermine each other, each vying for verisimilitude. Realistically both of them present the truth – the pipe resembles an object in the real world, whilst the sentence reiterates that this image is not an object of the real world.

Magritte argued “a painting was most successful when it defied the viewer’s habitual expectations and resisted any logical explanation or verbalization.”[12] The use of everyday objects in Surrealism is fundamental to the refutation of perceived normality. Manipulation of the everyday is also a theme of nonsense works, the tea party in Alice in Wonderland for example is an event in which specifically Victorian social expectations are warped by illogicalities. The irrational loops back on itself to reveal the arbitrariness and absurd normality of ‘the tea party.’ As in Magritte’s work where crucially the “explicitly rendered image of a pipe cannot be trusted. [and] is a treacherous friend that masquerades as the real object”[13] nonsense deals with the treachery of reality. According to Magritte the interaction of text and image in the space of our minds “is not the calm territory of unified and consistent thought, but is rather the territory of illogicities, doubts and surprises, where image and language mix only antagonistically, if at all.”[14] Nonsense is certainly not a “calm territory” – in many ways nonsense literature is this cerebral plane of interaction between antagonistically competing senses.

Perhaps the most nonsensical and Surrealist space is that of the dream. In dream the unconscious and conscious mind interact to produce an unregulated reality. Luis Buñuel’s 1972 film Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeoisie[15] explicitly deals with this boundless space, in order to parody the senselessness of specifically bourgeoisie social conventions. The structure of the narrative represents the fragmented subjective processing of reality, blending the real with absurdity in a way that resembles the nonsense of the dream world. Magritte considered his artwork “an act of visual thought”[16] – Buñuel’s film is also a visualization thought process, mimetic of an interior reality projected onto the real world. The nonsense of Buñuel’s work derives from the juxtaposition of the normal, the dining of a bourgeois group of friends, and the ridiculous, the interruptions of soldiers, political activists and the police, to name but a few. Within the tempestuous space of the film the characters are subjected to the violence of their subconscious; whole scenes are reinterpreted as dreams after they have occurred. Through the emphatically Freudian and bizarre representation of the soldier’s dream Buñuel satirizes and undermines the notion of ‘the dream.’ The vagueness of temporality in the space of the dream is highlighted in the constant chiming of a clock in the background. The soldier describes being “here,” a proximally indefinite space, deictically known only to him. The dream is thus both timeless and immaterial and so is equated with a kind of limbo state. The obviousness with which Buñuel alludes to death, as dirt is shovelled onto an unknown body is uncannily humorous. The dream becomes an allegory of the Oedipus complex as the protagonist forsakes a past lover to find his mother “among the shadows.” Interpretation of the dream is imposed on the viewer simply because it lends itself to such an overtly Freudian narrative.

For Buñuel it becomes nonsensical to separate dream from reality, the two are inextricably linked; as Bergson states, “the plane of dream, or dilated memory, is just as real as the plane of action.”[17] The scene feels particularly surreal in that it is introduced as “a very nice dream.” The absurdity thus also arises from the treatment of the dream as an anecdote. It feels jarring to the viewer as what is recounted is wholly personal. The dreamscape is a space of the indefinite past where memory functions nonsensically. Buñuel treats the unconscious as a place of “free volleying thought”[18] undeterred by reason. This is why the dream is so forcibly and violently crying out for interpretation by the viewer, but this would simply privilege reality and render the dream subservient to it. In actual fact Buñuel sees both reality and the dream as equal in the status of their interpretation of reality, both as pastiche of “haphazard chance meeting and ideas and visions.”[19] Carroll has a similar sense of the dream, as in his diary he writes “we often dream without the least suspicion of unreality: ‘sleep hath its own world,’ and it is often as lifelike as the other.”

The binary of interior and exterior realities is reflected in the dual consciousness of Haruki Murakami’s protagonist in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World[20]. The difficulty in defining the genre of Murakami’s novel stems from it’s postmodern rejection of categorization, thus it is a pastiche of different styles including sophisticated surrealism, nonsense literature, science fiction, detective and film noir. The conscious/unconscious binary that is explored in Alice in Wonderland, mapped and derided in The Treachery of Images and Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeousie is “radically dismantled”[21] in the novel. The narrator has a split consciousness that resides in two separate narratives and seemingly separate worlds. His psyche split between a futuristic ‘hard-boiled wonderland’ and the nonsensical fantasy land ‘the end of the world’ the protagonist “is made to become his unconscious, to inhabit his unconscious/to be inhabited by his unconscious.”[22] If the unconscious is a space of secrets lost to the conscious Murakami creates a world in which the subject itself becomes a lost object. The narration begins in a nonsensical elevator; a journey somewhat similar to Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole where all sense of space and time is distorted as “all sense of direction simply vanished.” The use of modal lexis adds to an uncertainty of time and space: “it could have been going down…Maybe I’d gone up…Maybe I’d circled the globe.” The narrator’s blasé treatment of his induced vertigo is reminiscent of the casualness with which Alice accepts her fall. Surrealists saw the displacement of subjective space as an experience synonymous with religious ecstasy. Masson describes such a moment occurring in the mountains of Montserrat in Barcelona:

The sky itself appeared to me like an abyss, something which I had never felt before – the vertigo above the vertigo below. I found myself in a sort of maelstrom, almost a tempest, and as though hysterical. I thought I was going mad.[23]

The space of the elevator is reminiscent of this in its stasis of both elevation and the feeling of being underground. Although Murakami’s narrator is not exposed to the violent “maelstrom” of Masson’s description, he experiences a similar subjective displacement: “I didn’t even know if I was moving or standing still.”

The nonsensical space of the elevator induces a distortion of the senses; the narrator “ventured a cough, but it didn’t echo anything like a cough.” The narrator’s warped sensory perception of reality thus provokes a kind of madness.. As the protagonist is “hermetically sealed in a vault” his inner consciousness is detached from the outside reality. The result of subjective isolation is that we cannot rationalize and assimilate our behavior within the structure of the policed social system and so it seems we are “mad.” The narrator absurdly notes the elevators capacity for “an office…a kitchenette…three camels and a mid range palm tree” as well its lack of switches, or in fact anything that resembles an elevator. Yet he merely questions how “this elevator could have gotten fire department approval.” The narrator’s follow up statement that “there are norms for elevators after all” reemphasizes his nonsensical observations. Although one can return from the chaos of Alice’s wonderland it seems that “Murakami’s narrator is fully at the mercy of forces preceding and exceeding him.”[24] The narrator has very little agency reflected in the image of him “stationary in unending silence, a still life: Man in Elevator.” The imagery of the title of the novel ‘hard-boiled’ crucially evokes the dynamic binary state (reminiscent of a Freudian separation of the conscious/unconscious) of an egg, separated unto itself between yolk and white. And yet Wonderland is a space without boundaries, without reason or structure. Thus the hard-boiled reality may seem from the outside permanently dual, inside it is a world ruled by chaos and nonsense.

Through the ‘underground’ worlds of dreaming and the unconscious, nonsense and Surrealism destabilize the boundaries of ontological certainty. Nonsense becomes a space where the chaos of representation and meaning is liberated. Carroll meditates “when we are dreaming…do we not say and do things which in waking life would be insane?”[25] None of the texts in this anthology are stable entities; they are liberations of the chaos of reality, necessarily thoughtful and wholly playful.

Footnotes:

[1] Kevin Jackson, ‘A-Z of Alice in Wonderland,’ The Independent (2010) http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/az-of-alice-in-wonderland-1902684.html [accessed 01 July 2015] (Para 19)

[2] Laura Mulvey, ‘Pandora’s Box: Topographies of Curiosity,’ in Fetishism and Curiosity (London: British Film Insitute and Indiana University Press, 1996) pp. 53-65 (pg. 60)

[3] ibid

[4] Katharine Conley, ‘Through the Surrealist Looking Glass: Unica Zurn’s Vision of Madness,’ in Automatic Woman: The Representation of Woman in Surrealism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996) pp.79-113 (pg. 100)

[5] Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (London: Wordsworth Editions 2001) See Appendix I. NB. All future references from this edition unless stated otherwise

[6] Gillian Beer, ‘Dream Touch,’ Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, (2014) http://www.19.bbk.ac.uk/article/viewFile/702/1018 [Accessed 1st July 2015] (pg.6)

[7] Jean-Jacques Lecercle, Philosophy of Nonsense. Jstor (1994) http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3829400?sid=21106165925903&uid=2129&uid=70&uid=4&uid=3739216&uid=2 [Accessed: 19 March 2015] (pg. 36)

[8] ibid

[9] Fiona Bradley, ‘Surrealism,’ Movements in Modern Art (London: Tate Gallery Publishing Ltd, 1997) pg. 13

[10] Sigmund Freud, Dream Psychology. Translated from German by M. D. Eder. Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org [Accessed: 1st July 2015] pg. 279

[11] René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (This is not a Pipe) c.1928-1929, Oil on Canvas, 63.5cm x 93.98 cm, Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, USA. See Appenidix II

[12] Gerrit Lansing, ‘Rene Magritte’s ‘The False Mirror:’ Image Versus Reality,’ Notes in the History of Art, Vol.4. No.2/3 (1985) http://www.jstor.org/stable/23202433 [Accessed 30th May 2015] pp 83-84 (pg. 84)

[13] ibid

[14] Robin Greenly, ‘Image, Text and the Female Body: Rene Magritte and the Surrealist Publications,’ Oxford Art Journal, Vol.15. No.2 (1992) http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360500 [Accessed 30th May 2015] pp.48- 57(pg. 52)

[15] Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeoisie, 1972 [Film, DVD] Directed by Luis Buñuel. France: 20th Century Fox. See Appendix III. Nb Quotations are from this film unless stated otherwise

[16] Suzanne Guerlac, ‘The Useless Image: Bataille, Bergson, Margritte,’ Representations, Vol.97. No.1 (2007)

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rep.2007.97.1.28 [Accessed: 30th May 2015] pp. 28-56 (pg.39)

[17] ibid pg.43

[18] Anna Balakian, Surrealism: The Road to the Absolute (New York: The Noonday Press, 1959) pg. 154

[19] ibid

[20] Haruki Murakami, Hard Boiled Wonderland and The End of the World. Translated from Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum. (London: Vintage Books, 2001) See Appendix IV. NB. All further quotations are from this book unless stated otherwise

[21] Jonathan Boulter, Melancholy and the Archive: Trauma, Memory, and History in the Contemporary Novel (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011) pg. 70

[22] ibid

[23] David Lomas, ‘Vertigo: On Some Motifs in Masson, Bataille and Caillois,’ in Surrealism: Crossings/Frontiers, ed. Peter Collier (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2006) pg. 91

[24] Jonathan Boulter, Melancholy and the Archive: Trauma, Memory, and History in the Contemporary Novel (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011) pg. 62

[25] Gillian Beer, ‘Dream Touch,’ Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, (2014) http://www.19.bbk.ac.uk/article/viewFile/702/1018 [Accessed 1st July 2015] (pg.6)

Bibliography

Balakian, Anna Surrealism: The Road to the Absolute (New York: The Noonday Press, 1959) pg. 154

Beer, Gillian ‘Dream Touch,’ Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, (2014) http://www.19.bbk.ac.uk/article/viewFile/702/1018 [Accessed 1st July 2015]

Bradley, Fiona ‘Surrealism,’ Movements in Modern Art (London: Tate Gallery Publishing Ltd, 1997)

Boulter, Jonathan Meloncholy and the Archive: Trauma, Memory, and History in the Contemporary Novel (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011)

Conley, Katharine ‘Through the Surrealist Looking Glass: Unica Zurn’s Vision of Madness,’ in Automatic Woman: The Representation of Woman in Surrealism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996) pp.79-113

Freud, Sigmund Dream Psychology. Translated from German by M. D. Eder. Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org [Accessed: 1st July 2015]

Greenly Robin, ‘Image, Text and the Female Body: Rene Magritte and the Surrealist Publications,’ Oxford Art Journal, Vol.15. No.2 (1992) pp.48- 57

Guerlac, Suzanne ‘The Useless Image: Bataille, Bergson, Margritte,’ Representations, Vol.97. No.1 (2007) http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rep.2007.97.1.28 [Accessed: 30th May 2015] pp. 28-56

Jackson, Kevin. ‘A-Z of Alice in Wonderland,’ The Independent (2010) http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/az-of-alice-in-wonderland-1902684.html [accessed 01 July 2015] (Para 19)

Lansing, Gerrit ‘Rene Magritte’s ‘The False Mirror:’ Image Versus Reality,’ Notes in the History of Art, Vol.4. No.2/3 (1985) http://www.jstor.org/stable/23202433 [Accessed 30th May 2015] pp 83-84

Lecercle, Jean-Jacques Philosophy of Nonsense. Jstor http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3829400?sid=21106165925903&uid=2129&uid=70&uid=4&uid=3739216&uid=2 [Accessed: 19 March 2015]

Lomas, David ‘Vertigo: On Some Motifs in Masson, Bataille and Caillois,’ in Surrealism: Crossings/Frontiers, ed. Peter Collier (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2006)

Mulvey, Laura. ‘Pandora’s Box: Topographies of Curiosity,’ in Fetishism and Curiosity (London: British Film Insitute and Indiana University Press, 1996) pp. 53-65

Anthology

Appendix I

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next. First, she tried to look down and make out what she was coming to, but it was too dark to see anything; then she looked at the sides of the well, and noticed that they were filled with cupboards and book-shelves; here and there she saw maps and pictures hung upon pegs. She took down a jar from one of the shelves as she passed; it was labelled `ORANGE MARMALADE’, but to her great disappointment it was empty: she did not like to drop the jar for fear of killing somebody, so managed to put it into one of the cupboards as she fell past it.

`Well!’ thought Alice to herself, `after such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling down stairs! How brave they’ll all think me at home! Why, I wouldn’t say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!’ (Which was very likely true.)

Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end! `I wonder how many miles I’ve fallen by this time?’ she said aloud. `I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth. Let me see: that would be four thousand miles down, I think–‘ (for, you see, Alice had learnt several things of this sort in her lessons in the schoolroom, and though this was not a very good opportunity for showing off her knowledge, as there was no one to listen to her, still it was good practice to say it over) `–yes, that’s about the right distance–but then I wonder what Latitude or Longitude I’ve got to?’ (Alice had no idea what Latitude was, or Longitude either, but thought they were nice grand words to say.)

Presently she began again. `I wonder if I shall fall right through the earth! How funny it’ll seem to come out among the people that walk with their heads downward! The Antipathies, I think–‘ (she was rather glad there was no one listening, this time, as it didn’t sound at all the right word) `–but I shall have to ask them what the name of the country is, you know. Please, Ma’am, is this New Zealand or Australia?’ (and she tried to curtsey as she spoke–fancy curtseying as you’re falling through the air! Do you think you could manage it?) `And what an ignorant little girl she’ll think me for asking! No, it’ll never do to ask: perhaps I shall see it written up somewhere.’

Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again. `Dinah’ll miss me very much to-night, I should think!’ (Dinah was the cat.) `I hope they’ll remember her saucer of milk at tea-time. Dinah my dear! I wish you were down here with me! There are no mice in the air, I’m afraid, but you might catch a bat, and that’s very like a mouse, you know. But do cats eat bats, I wonder?’ And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, `Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, `Do bats eat cats?’ for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it. She felt that she was dozing off, and had just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, and saying to her very earnestly, `Now, Dinah, tell me the truth: did you ever eat a bat?’ when suddenly, thump! thump! down she came upon a heap of sticks and dry leaves, and the fall was over.

Source: Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking-Glass (London: Wordsworth Editions 2001)

Appendix II

Source: René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (This is not a Pipe) c.1928-1929, Oil on Canvas, 63.5cm x 93.98 cm, Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, USA. Available to view at: http://artdaily.com/news/19062/Magritte-and-Contemporary-Art%20–%20The-Treachery-of-Images#.VW1zDkJRfdk

Appendix III

Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeoisie, 1972 [Film, DVD] Directed by Luis Buñuel. France: 20th Century Fox.

Appendix IV

THE ELEVATOR CONTINUED its impossibly slow ascent. Or at least I imagined it was ascent. There was no telling for sure: it was so slow that all sense of direction simply vanished. It could have been going down for all I knew, or maybe it wasn’t moving at all. But let’s just assume it was going up. Merely a guess. Maybe I’d gone up twelve stories, then down three. Maybe I’d circled the globe. How would I know?

Every last thing about this elevator was worlds apart from the cheap die-cut job in my apartment building, scarcely one notch up the evolutionary scale from a well bucket. You’d never believe the two pieces of machinery had the same name and the same purpose. The two were pushing the outer limits conceivable as elevators.

First of all, consider the space. This elevator was so spacious it could have served as an office. Put in a desk, add a cabinet and a locker, throw in a kitchenette, and you’d still have room to spare. You might even squeeze in three camels and a mid-range palm tree while you were at it. Second, there was the cleanliness. Antiseptic as a brand-new coffin. The walls and ceiling were absolutely spotless polished stainless steel, the floor immaculately carpeted in a handsome moss-green. Third, it was dead silent. There wasn’t a sound— literally not one sound— from the moment I stepped inside and the doors slid shut. Deep rivers run quiet.

Another thing, most of the gadgets an elevator is supposed to have were missing. Where, for example, was the panel with all the buttons and switches? No floor numbers to press, no DOOR OPEN and DOOR CLOSE, no EMERGENCY STOP. Nothing whatsoever. All of which made me feel utterly defenceless. And it wasn’t just no buttons; it was no indication of advancing floor, no posted capacity or warning, not even a manufacturer’s nameplate. Forget about trying to locate an emergency exit. Here I was, sealed in. No way this elevator could have gotten fire department approval. There are norms for elevators after all.

Staring at these four blank stainless-steel walls, I recalled one of Houdini’s great escapes I’d seen in a movie. He’s tied up in how many ropes and chains, stuffed into a big trunk, which is wound fast with another thick chain and sent hurtling, the whole lot, over Niagara Falls. Or maybe it was an icy dip in the Arctic Ocean. Given that I wasn’t all tied up, I was doing okay; insofar as I wasn’t clued in on the trick, Houdini was one up on me.

Talk about not clued in, I didn’t even know if I was moving or standing still.

I ventured a cough, but it didn’t echo anything like a cough. It seemed flat, like clay thrown against a slick concrete wall. I could hardly believe that dull thud issued from my own body. I tried coughing one more time. The result was the same. So much for coughing.

I stood in that hermetically sealed vault for what seemed an eternity. The doors showed no sign of ever opening. Stationary in unending silence, a still life: Man in Elevator.

Source: Haruki Murakami, Hard Boiled Wonderland and The End of the World. Translated from Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum. (London: Vintage Books, 2001)